Bilingual dictionaries can be dangerous things, we were told at school – especially if you’re still at beginner level in one of the languages and you haven’t yet developed a “feel” for it. On the other hand if you know the languages well, dictionaries can be useful and interesting. If I look up a word or phrase in a paper dictionary it takes me longer, but I find myself drawn into reading lots of other interesting words and phrases or idioms on that same page. For speed I prefer to use an online dictionary, but then I only read the specific word or phrase I’m looking for.

In my blog post Realizing childhood dreams, I wrote about my fascination with language from a young age, and about how I tried (in vain) to teach myself French from an old text book. That’s how I discovered the hazards of translating word for word.

I had to wait until age 11 for my first French lessons, when all the mysteries would be solved, I thought. In the second week I was struggling with my homework, trying to work out the meaning of “Il y a” which started every sentence on the first page of the textbook. “He there has”? I remember seeing a picture of a tree and the caption “Il y a un arbre”. Then there was “Il y a une maison”, “Il y a un chien”, “Il y a un chat”… What could possibly go in front of “a tree”? Apparently something which could also go in front of a house and a dog and a cat. I was overthinking it. My Dad, trying to help, said he’d learnt it at school …. but he couldn’t remember what it meant. It wasn’t in the dictionary either, and the teacher didn’t want to explain in English; we were supposed to pick up the meaning by hearing it a lot. It means “there is…” or “there are…”

Years later when I was teaching languages, I was amazed at some of the translations my students produced. It seemed that because the source language was “foreign”, it didn’t have to make sense in the target language. “Howlers” were produced by choosing the wrong word from the dictionary, for example “Elle était croix.” Some students applied English word order to German sentences.

After a few years’ teaching it was time for a change. Working as a translator for the UK subsidiary of a German medical company, I came across the translations which had been produced before I started work there. In the absence of an English native speaker with a good understanding of German, some glossy leaflets had been produced in English by someone at the German office who had a dictionary. They hadn’t consulted an English native speaker before printing them. Hundreds of glossy leaflets were delivered to our office ready for distribution at a hospital doctors’ conference, and had to be put in the bin to save embarrassment. Part of a picture of an operating table should have been labelled “The pelvic section”. Instead of that it was labelled “The buttock plate”. A picture of two instrument trolleys had the caption “Instrument wagon, 2 of it with brake”.

Tourist English (or indeed Tourist Any-Other-Language) can provide “opportunities” for the unwary to change the meaning of the original by using a dictionary. Before giving any more examples I should emphasize that I’m not poking fun at people for trying to provide translations! As a language learner myself I’ve made plenty of howlers. I’ll start with one of my own mistakes.

In this one I’m in an Austrian hotel, where I’m staying with my husband and 2 year-old daughter in 2007. Our daughter is playing with her soft toy laborador.

Daughter: “Oh no! Monty stuck.” She’s managed to invent a code for the room safe and lock him inside. She doesn’t remember the code, needless to say.

Me, ‘phoning reception: “….meine Tochter hat ihren Hund im Safe eingeschlossen.”

Receptionist: (long pause) “Ach so (sigh of relief), Sie meinen ein Kuscheltier (soft toy)! Hilfe kommt sofort…” (despatches porter to let the dog out).

Well, we had all got into the habit of treating Monty as though he was real.

Anyway, on the subject of room safes, the author of our hotel information leaflet had looked up the word for “hotel room safe” in English. They had written down the first word they saw for that dictionary entry: it must have been “strongroom”. You had to pay a “bail”, rather than a deposit, for the key to this strongroom. Similarly, the French version promised their guests a “chambre forte”:

In their welcome message the hotel owners appeared a little bit too obliging:

And we weren’t quite clear about the system for making ‘phone calls:

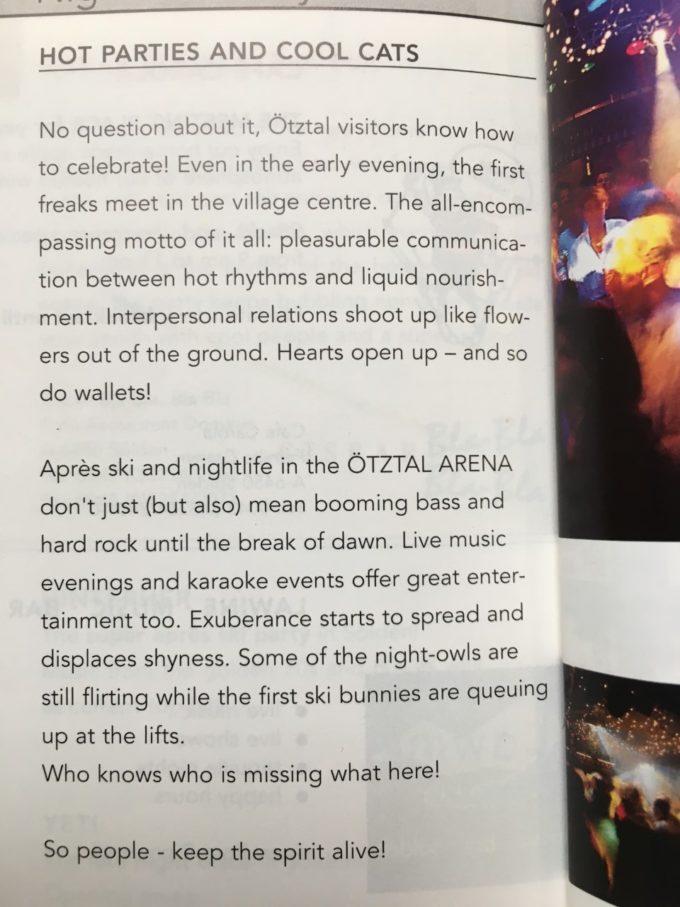

Long before that 2007 holiday, in 1999, my husband and I went on our first holiday together. It was Austria this time as well. The village holiday guide included this advice for those planning to enjoy the local nightlife:

My husband’s favourite bit is “Hearts open up – and so do wallets”.

The same holiday guide has some more specific tips about where to go in the evening:

So here we’re told to go next door for a Schmankerl with the dexterous staff. At the airport on the way home we found out what a Schmankerl actually was:

The translator of the “Hot parties” section writes: “So people – keep the spirit alive!”. No need for us to do this – he or she has kept the spirit of the original text alive themselves. But the language and images used in Austrian holiday advertising are rather different from those used in English – the Austrian style is rather “naïve”, and equivalent copy in English is more subdued. This was probably even more the case on our visit 19 years ago. The writer has translated word for word, choosing the wrong word from the dictionary nearly every time. I hope they keep doing this!

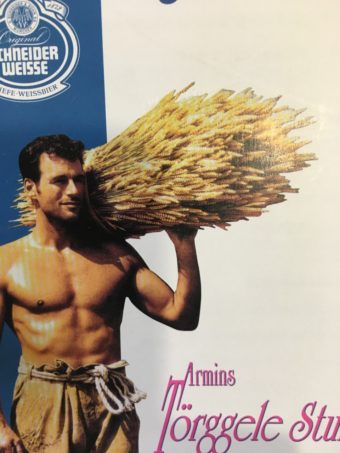

To give an idea of the advertising style we kept seeing, here’s an advert for one of the café/bars in the village:

The text seems to go well with this.

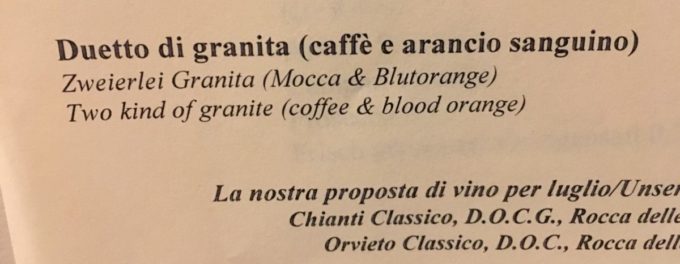

Translation howlers seem funnier when they’re printed somewhere that looks official. If they were handwritten they wouldn’t be as amusing. If they’re in a glossy brochure or leaflet, or better still on a noticeboard, they look very earnest, as though they’re ordering us to take them seriously. Restaurant menus can be fun. Here’s a dessert for diners with strong teeth, found last year on holiday:

If you’d like to read a whole collection of translation “howlers”, I’d recommend this book by Charlie Croker:

It’s not the sort of book you’d want to read from cover to cover in one go. It’s best just to read a snippet or two when you’re feeling a bit fed up, and your mood will soon lighten. I find that these things are even better when they’re shared. I’ve read them out loud to friends and colleagues and we’ve ended up aching with laughter.

It can take language learners, like me, a long time to realize that there isn’t always an exact equivalent for a word in another language. For example, in German the word “gemütlich” means more than “cosy” in English. It’s often used to describe a place which hasa warm and welcoming atmosphere. The German word “Torschlusspanik” means literally “The panic of the closing of the gate”, and it refers to a loss of opportunities as we get older, such as “the race against the biological clock” for a woman. But why should there be an exact equivalent for each word? Languages weren’t developed by someone leafing through a bilingual dictionary. We need the context of a word to get the meaning, and we translators need to get away from the words used in the source language so that we can reformulate the meaning in the target language.

Some modern English phrases could be difficult for a translator. Phrases which could produce “howlers” are the “Disabled toilets” signs, and the signs on escalators which tell you “Dogs must be carried”. Do you have to be carrying a dog to go on there? It depends on whether you stress the word “dogs” or the word “carried”. The latest equivalent of “Thank you” is “Nice one”, a possible “stumbling block” (idiom alert) for a translator who hasn’t kept up to date with the way English is changing.

I came across lots of stumbling blocks when I did an interpreting course. If I concentrated on the strings of words, instead of waiting and conveying the “message”, I sometimes ended up stuck, travelling down a road where I didn’t want to be. Stumbling blocks can also be unknown idioms. They pop up everywhere (like “stumbling blocks”). If you recognize the idiom you can try to find an equivalent idiom or phrase in the target language, but if you translate every word you might end up with something baffling. In French, if you’re kept waiting by someone you “act like a leek” (faire le poireau; be stood up in English), and if you faint you “fall into the apples” (tomber dans les pommes).

We do need to be accurate when we translate. But literal translations can weaken the meaning or change it altogether. We should always translate into our native language, or get our efforts checked by a native speaker. If we can convey the “spirit” or “message” of the source language, we can give it a new life in the target language. But sometimes it can be fun for the casual reader if we don’t.

Leave a Reply