In my recent blog post “From revolutionary to biscuit entrepreneur”, I mentioned how exciting it is to see a friend being interviewed on TV. It’s also exciting to see a friend’s name on the front cover of a book, and that’s how it was back in 1992, when my friend Bernhard Thill (alias Felix) had his first book published. He co-wrote the book with the writer Astrid Fritz. It’s about his home town of Freiburg in the Black Forest, southwest Germany: “Unbekanntes Freiburg: Spaziergänge in die Geschichte und die Welt der Sagen und Legenden.” Walks into the history, myths and legends of Freiburg.

Freiburg is Germany’s sunniest, greenest city. I spent a happy year there as a student, on a scholarship from the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service), so I’m interested to read Felix’s book. Working together with Astrid Fritz, he describes 13 walks in Freiburg which uncover stories from the past – myths and legends behind (or underneath) churches, museums, gravestones…They’re extraordinary anecdotes about ordinary people; some sad, some funny. New stories are always coming to light and the book was completely updated in 2015. Mine’s the first edition:

…and it’s even a signed copy:

….yes, a great memory of student days.

The authors explain the aims of the book in the introduction. When we go on holiday we expect to discover secrets behind what we see. But when it comes to our home town, we take it all for granted. We go shopping or we travel to work without giving any thought to the hidden surprises and mysteries around us. Unbekanntes Freiburg brings quirky myths and legends back to life and allows us to view the city with new eyes. I’ve had a similar experience re-exploring Pau, France, with our friend who lives there and likes to investigate her surroundings.

Unbekanntes Freiburg is aimed at those who live in Freiburg and want to find out more about the city, as well as at those tourists who find traditional guidebooks too superficial or too dry. I don’t fall into either of those categories. For me, it’s a fascinating book about a city I’m familiar with but I don’t live there, so I’m just “dipping in”. Some of the stories would be similar in many other cities too – such as the everyday life of a medieval university student, the punishments dished out to medieval criminals, or the brutal treatment of “witches”.

In this post I’m giving a “taster” of Felix’s book. I’ve picked out a few interesting snippets, summarized them and added photos and the odd comment of my own. The sketches are taken from the book, and the source for them was 19th and 20th century editions of the academic journal “Schau-ins-Land” (Schauinsland, lit. “Look into the country”, is the local mountain). I’m starting with the unique “Freiburger Bächle”, and here I’ve added some extra information. Then I move on to Freiburg University, which makes a huge contribution to the city’s cultural life and easy-going atmosphere. Then there are some quirky stories about witches, an old pharmacy, a medieval brothel and a medieval hospital. I’ve finished off with the Münsterplatz and the Münster itself, at the centre of Freiburg life.

The Freiburger Bächle

I’ve heard Freiburg referred to as a “Little Venice” because of these “brooks” which are a Freiburg landmark. The word “Bächle” is made up from the German word “Bach” (stream) plus the local (Alemannic) diminutive ending. The streams are formed by directing water from the city’s river Dreisam into narrow channels. The water flows on a slight downward incline through most of the streets in the medieval Old City (Altstadt).

If you live in Freiburg for a few years you’re bound to fall into a Bächle at least once. An old superstition going back to at least the 13th century dictates that if you do, you’ll have to marry a Freiburger! The original function of the Bächle was quite different. They formed the water supply for the city centre – especially useful for putting out the house fires which were common in medieval times.

It’s thought that the Bächle were already in existence when the city was founded in about 1120. They acted as an artificial water course to irrigate pasture land. When the first buildings of “Friburgum” were constructed, the water course was left in place to flow through the settlement and then out onto the fields. This solved the problem of supplying water to the town when the ground water was about 12 metres below the earth.

Here’s a drawing by Gregorius Reich, a monk in a monastery near Freiburg. He drew it in 1495. He had no idea that he was providing us with the first picture of “Friburgum”.

All too often, the Bächle were used as a sort of rubbish disposal system. In 1552 a regulation was published: “..soll nymandt khein mist, strouw, stain…inn die baech schuetten noch werffen..” Nobody should tip or throw dirt, straw, stones into the Bächle. There must have been a need for that rule.

In the 19th century the water network was modernized and the Bächle were moved from the centre of the roads to the sides, where they posed less of a hazard. They came into their own again in 1944, when water pipes were destroyed during an air raid and the Bächle were once more used to extinguish fires.

Since 1973 the city centre has been reserved for pedestrians and trams. So the famous Bächle have become more visible. You can even buy the kids a “Bächle-Boot” from a nearby kiosk, to coax along the channels attached to a long piece of string.

The Bächle are drained twice a year as part of their maintenance, and there are 2 people working as dedicated “Bächleputzer” who clean them twice a day. So they’re well looked after. I’ve never seen any rubbish in them.

Everyday life at uni in 1460

Freiburg University was founded in 1457. By 1460 there were 7 professors and 110 students studying philosophy, medicine, law and theology. They were expected to devote themselves to the accumulation of knowledge and their lives were strictly regimented. There were rules governing the use of Latin and the academic gowns they had to wear.

These rules didn’t go down very well with members of the nobility, who were used to sporting their own fine fabrics with intricate embellishments. It seems there was not much critical thinking: until the end of the 18th century, students had to learn summaries of all lectures by heart to prepare for tests every evening. Here’s a lecture:

New students had to endure cruel initiation ceremonies which the university authorities found impossible to stop – such as having a tooth forcibly removed by their peers!

Most students lived in hostels and had to get up at 4 am and go to bed at 9 pm. The little free time they had was filled with religious plays or supervised walks. Students who managed to get lodgings with professors or relatives were looked upon with envy. Their landlords needed the rent, so they turned a blind eye when their charges went dancing or drinking. These weren’t their only transgressions: in 1516 the city complained to the university that students were fishing without a permit in the river Dreisam … and keeping wolves and foxes.

Now the Universität Freiburg has about 20,000 students and I don’t think any of them keep wolves.

The sad story of a kind “witch”.

Catharina Stadellmenin lived at Schiffstrasse 14 in the “Altstadt” until her death in 1599. In common with many other women of her time, she was monitored with suspicion by her nosy neighbours and denounced as a witch. Her husband was a violent man and the only thing she did “wrong” was to try to lead an independent life. She earned herself a few pennies by taking in student lodgers. One of the lodgers was very poor, so he ran errands for her instead of paying rent. Catharina met up regularly with her women friends. One of her neighbours spotted one of these friends entering and leaving the house at 8 or 9 at night, when honest women should apparently have been at home – and to cap it all, the women were seen dancing. Then another suspected witch revealed Catharina’s name under torture and that’s how her fate was sealed. She was beheaded and burned. In that year alone, 12 Freiburg women were murdered for being “witches”.

In the chapter “Geographie der Grausamkeit” there are horror stories of people being tortured to get confessions, hands chopped off for theft, hangings…

The Glocken-Apotheke

This pharmacy sited near the Münsterplatz has been in existence since 1652. Until the 17th century, pharmacies used to sell herbal remedies and rare objects. A price list from the year 1607 lists such delights as roasted worms, human flesh and wild cat fat.

House of Fleeting Pleasure (zur kurzen Freud’)

In medieval times there was a brothel, or Haus “zur kurzen Freud’” (house of fleeting pleasure) on the Karlsplatz near the Münsterplatz. This “Frauenhaus” was run by the local executioner. Understandably not many people wanted to hang out with this guy. But that didn’t stop lots of men from sneaking into his den of sin. There were some wild goings-on there, and the executioner was once charged a large fine because he had “bey nacht und nebel den weybern mit steinen in ir hus geworfen”. He’d been throwing stones into the house at the women, day and night.

The women were not very popular. They had to wear special bonnets so that they could be recognized everywhere they went. If they got out of hand they were punished by being made to pull carts of manure or having their plaits or even their ears cut off.

Heiliggeist-Spital (Holy Ghost Hospital)

The area between the Kaiser-Joseph-Strasse and the Münsterplatz was the site of the Heiliggeist-Spital until 1823. It was a municipal hospital which cared for all sick people, and its history can be traced back to the 13th century. Even old people who could afford the fees were given a place here for their last days.

The complex included a cemetery, chapel and prison. No distinction was made between rich and poor patients, but eventually space ran out and a separate hospital was founded for poor people. Patients who didn’t follow hospital regulations were punished by losing their wine entitlement, or they had to eat in the children’s room or sleep on the floor. Documents from the year 1557 reveal that even foreigners were taken in: “Der Landfahrer aus der Insel Amerika hat sich nun bei acht Tagen im Spital aufgehalten. Man besorgt, dass er darin erwarme.” “The wanderer from the island of America has been staying in the hospital now for 8 days. We are making sure he warms up there.” Well, after some of the other stories it’s a relief to read about compassion.

The Münsterplatz

The Münsterplatz or Cathedral Square has always played a central role in Freiburg life. It started off as a cemetery containing layers of human remains from plague times. In 1744 the cemetery was moved because of overcrowding, to a site to the north of the city (Alter Friedhof).

Some small shops were built into the cemetery wall and there was a dwelling for a night watchman. We know that music was not allowed on the site in the 15th century and neither was “das Eiersammeln am Tage nach der Hochzeit (1459). You weren’t allowed to collect eggs there the day after your wedding (was this a superstition to do with fertility?). The slaughterhouse and the theatre were accommodated together, under the same roof in a building known as the “Metzig” until 1785. Presumably the smell from the slaughterhouse didn’t deter the theatre goers.

Even in more recent times, extraordinary things have happened on the Münsterplatz. In November 1944 most of its buildings were destroyed in the Second World War bombing raid on Freiburg, but amazingly the Münster itself was spared. A couple of years later the ruins of the buildings were used as a back drop for a passion play, providing an impressive – and inexpensive – setting. Eventually these medieval buildings were rebuilt as near-identical replicas.

Nowadays the Münsterplatz is the site of the colourful daily market where you can buy fresh regional products direct from local bakers (like Teegebäck Raffael) and farmers.

The Münster

The minster, acclaimed as a masterpiece of Gothic architecture, was built between 1200 and 1500. Its sandstone spire alone is 46 metres high, and its filigree openwork gives a delicate lacework effect. You can actually see the sky through the tower. Sometimes part of the spire is obscured because of renovation work.

The minster was financed from the proceeds from a silver mine in the Schauinsland mountain near Freiburg. The story goes that when the cathedral was finished, the families who had profited from the mine were keen to rediscover it. Despite their best efforts all they could find was an underground cave. A woman in white was sitting there at a table, a bunch of keys in her hand. She shouted to them that the silver would never be found again, that they should make themselves scarce, and since then nobody has dared to go looking for silver.

Like many cathedrals, the Muenster was used for many years as a multipurpose community hall (Mehrzweckhalle). In times of war it was used as storage space. The city council had some problems on the agenda at a meeting in 1816. There was concern about the inappropriate behaviour of worshippers. Dogs were being brought into the services against regulations. Officials were told they should not be embarrassed to chase the dogs out of the building or whack them with a special whip. One can only assume that these dogs weren’t sitting quietly as most dogs do nowadays in public places. Perhaps they weren’t bred to be cuddly companions, but more as a defence against attack.

The chapter on the Muenster starts like this: “Das Münster ist, als Ort des Glaubens, von jeher auch ein Ort des Aberglaubens in der Legenden gewesen; die Grenzen sind hier fliessend.” The Münster, as a place of faith, has always been a place of superstition as well; in this case the boundaries are fluid.” This becomes very clear as we read the chapter. The word Aberglaube (literally “but belief”) was first used in the later 15th century, meaning wrong (ie not Christian) belief or faith (Glaube). The authors concentrate on the strange and quirky aspects of the Muenster and leave more general art history to the many other books dedicated to this subject.

Gargoyles (Wasserspeier)

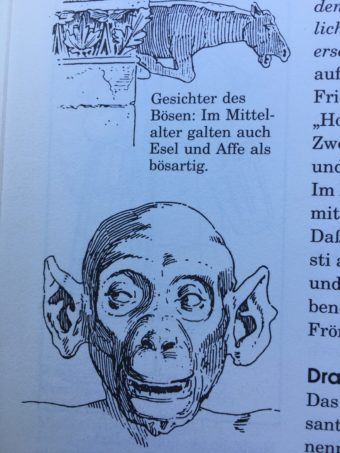

The evil–looking devils, monkeys, donkeys and other animals leaning over us on the outside of the Muenster were installed to defend the building from evil spirits. In medieval times people imagined that the devil was constantly attacking the building with an army of malicious creatures resembling sinister nocturnal birds. So the gargoyles would fight back, and “like” would be repelled by “like”- a heathen idea.

On a more realistic note, the gargoyles also divert the rainwater and slow down the deterioration of the stone, thus preserving the cathedral, so that was part of their purpose as well. It’s strange to see them mixed in with various “holy” figures.

The Noodle Bell (Spätzlesglock)

If you stand in the Münsterplatz on a Friday at 11 am, you’ll hear this very unusual bell. It originally served as a signal for housewives to put the water to boil for the Spätzle (traditional local noodles) for lunch. Cast in 1258, it’s the oldest prayer bell (Gebetsglocke) in Germany. A Latin prayer inscribed on its edge pleads for heavenly help whenever the bell is rung. And that’s where its role as a peace bell began. In medieval times it was rung as a fire warning, and now it rings out on 27th November every year in memory of the bombing of Freiburg in 1944.

The cheeky ox window (Der gefrässige Ochse)

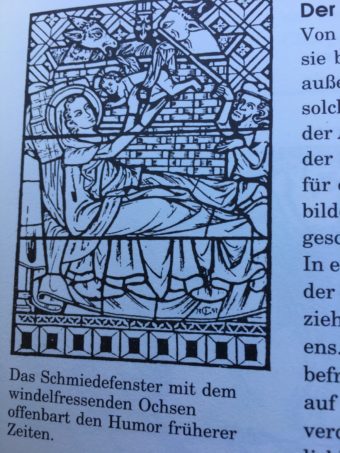

Medieval worshippers were persuaded that if they looked at the stained glass windows they would be protected from misfortune. So it’s no surprise that as well as biblical scenes for the more educated citizens, there were also scenes from folklore to attract the attention of a wider public. The guild of forge craftsmen (Schmiedezunft) sponsored an amusing example above the North Portal of the Muenster. It was an attempt to offer the uneducated medieval citizen access to salvation.

At first glance the window looks like a traditional Nativity scene. However, the obligatory ox has grabbed baby Jesus’ swaddling clothes and is lifting him up out of Mary’s arms. In an attempt to stop him, Joseph is whacking the ox on the nose with a stick.

The Tower (der Turm)

The tower became known as “der schönste Turm der Christenheit”. Its lace-like spire is especially beautiful. But its architect had the nerve to plan a better one somewhere else. So his eyes were gouged out and that was the end of that.

In the 17th century the Münster was hit by many storms. The tower was vulnerable to lightening strikes and caught fire several times. Tower watchmen were warmly dressed against the cold, and they had to carry a fire bucket.

During building works at the beginning of the 19th century, small anti-storm prayer notes were found in the tower. The prayers were recited while making the sign of the cross in the direction of the clouds. Two tiny bits of paper, 14 x 14cm, were actually edible blessings which had to be eaten for their effects to take place.

It wasn’t just the weather which posed a threat to the tower. The minutes from a city council meeting in 1562 report that some men had broken the rules and taken their “Weiber” (women) up the tower to party, jig about and dance. One of the men was locked up as a punishment.

The Muenster bells were blessed after casting and decorated with religious symbols. Until the 18th century they were rung to divert approaching storms. Apparently the tower wardens didn’t always take their duties seriously enough. We read in council minutes from 1720: “Den Turmwächtern ist ernstlich anbefohlen, dass sie fleissiger wider das Wetter läuten sollen.” The tower wardens were earnestly requested to ring the bells more vigorously against (bad) weather.

Everyday heroes (Helden des Alltags)

Last but not least, the final chapter of the book tells the story of some everyday heroes of Freiburg. They’re the excentrics who’ve added charm and character to the place: the student who used to walk on his hands at ceremonial concerts, or the couple who rode on a tandem to their wedding.

There will always be unconventional people around to make us smile. They might even provide us with some more quirky stories (skurrile Geschichten) for the next edition of Unbekanntes Freiburg.

Tourist Information Office

General information about visiting Freiburg can be found here.

Unknown Breisgau

Bernhard Thill (alias Felix) has just had another book published (April 2018): Unbekannter Breisgau, Streifzüge in die Geschichte und die Welt der Sagen und Legenden, paperback (Taschenbuch) published by Rombach. Forays into the history and myths and legends of the countryside around Freiburg. Sounds like a good reason to visit Freiburg and do some more walks…

Leave a Reply