If your child has more than one language you can have fun cooking in a minority language and learning a bit about the culture behind the food. When my daughter was a toddler we started by baking bread in English, our main language, and making breakfast in German or French. Now she’s 13 and we’ve had over 10 years of languages in the kitchen (well, on and off!). I’ve put together 7 hints for families who’d like to do something similar.

Here are the links to three other posts I’ve written about baking with kids: there’s French chocolate nuns, Epiphany cake, and Swedish cinnamon buns.

1. Buy a really good cookbook in a language you speak

…with mouthwatering pictures.

“Backvergnügen wie noch nie” by Annette Wolter with photos by Christian Teubner (1984). In English it means something like “The best fun you’ve ever had with baking”.

This is a top-selling baking book, despite the non-startling front cover. The instructions are really clear and there’s a photo with every recipe. The first section gives you all the basic cake recipes in detail, along with lots of helpful hints about German baking. After that the book covers an extensive range of recipes: cakes for entertaining; midweek baking, parties, family celebrations, desserts, Christmas, New Year, Easter, wholemeal baking, breads, “Grossmutters Backgeheimnisse” (Grandma’s baking secrets)… everything you could ever need.

If you have younger kids, or you need an easier level of language, you could buy a lovely children’s cookbook in that language. There are lots of recipes on the internet, but it’s much nicer to have a proper book to read and browse in.

Here’s a good website: cookingwithlanguages.com for children who are just beginning to learn English or Spanish. The subheading is “Let’s get children excited about learning languages!”

I’ve also heard a lot about cookery workshops for adult language learners, a great idea.

2. Remember the title “Backvergnügen” – have fun baking!

I recognized lots of the delicious German cakes in our book and I was keen to get started. I find baking relaxing and it engages all your senses: there’s the feel of the ingredients with their different textures, and the amazing smell as the cake starts to cook in the oven. You’re sampling a corner of it as soon as it’s cool enough not to burn your tongue. Then comes the best part, when you’re sharing the goodies with family or friends. Baking is creative and sociable – and much easier than cooking a full meal.

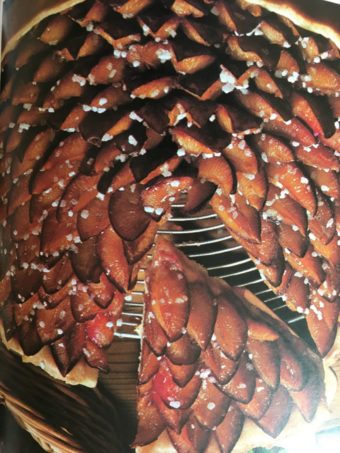

Baking has always been a fun way of creating a space to speak French or German with my daughter. The French or German recipe acts as a sort of “trigger” and it comes naturally to read the recipe and talk about it in that same language rather than translate it into English. At the same time we might be re-creating memories of eating special cake in cafes or at friends’ houses. This autumn I baked one of my favourite German cakes, Zwetschgenkuchen, or plum tray bake. Here’s what it looked like (photo from the above book):

The Zwetschgenkuchen brought back a happy memory of visiting some German friends I hadn’t seen for a long time. It was autumn, the plum season in Lübeck, North Germany. As I went in the front door I was greeted by my friends and by the welcoming smell of Zwetschgenkuchen drifting out of the oven. The cake had a thin sponge base, a dense covering of sliced plums and a sprinkling of cinnamon and sugar. And I had to eat it warm with Schlagsahne (whipped cream), drink coffee and catch up with my friends. Perfect.

3. Choose a yummy cake to make together

My daughter browsed in our new baking book and picked out a few recipes. We started with Schlesischer Streuselkuchen. For a start, the title is a great Zungenbrecher, or “tongue breaker”. Try saying it quickly, several times. It will get your tongue in a tangle.

4. Find out something interesting about the cake

Where does the recipe originate from? Schlesien (Silesia) was the eastern-most part of Germany before the end of the Second World War. After WW2 the Germans were expelled from there (one of those unimaginable ordeals) and it became part of Poland. The area now borders present-day Germany and the Czech Republic.

Back to more frivolous things. Traditional Silesian cakes are similar to Polish ones. The Streuselkuchen is like the Polish cheesecake I bought when I was “researching” my blog post about cheesecakes and Polish cakes in the UK. Poppy seed strudel is also part of the baking tradition in both countries. Streuselkuchen caught on in the rest of the German area as early as the 19th century. It’s known as Straeselkucha in the Silesian dialect.

5. On your marks, get set, baaake!

Here’s the recipe page in the book. Unfortunately I can’t make the print big enough to read, so if you’d like to make this cake you’ll need to buy this book, or a different one, or google Schlesischer Streuselkuchen.

Below I’ve picked out the most fun steps in the process of making the cake – the parts which kids will like the most.

There are three layers. The base layer is a brioche mixture, the middle layer is a sweet Quark (curd cheese) mixture and the topping is Streusel (crumble).

We made the brioche base with fresh yeast (“Hefe” in German), a much more interesting texture and smell than the dried sort.

You leave the mixture somewhere warm to let it rise (always fascinating), and then you roll it out onto a baking sheet

The sweet curd cheese layer makes the cake into a kind of cheesecake. In some recipes poppy seed or apple is mixed in with this middle layer. It looks so smooth…

You spread it onto the brioche layer

The Streusel topping is like British crumble, but with less flour so the result is more buttery with larger lumps. This is where you get your hands all sticky

You sprinkle the Streusel onto the Quark layer, and bake it in the oven

6. Now for the best bit: eat what you’ve made

This cake doesn’t need cream. No really, I think it’s better without, and I’m usually all for a swirl of Schlagsahne (a cloud of whipped cream). Just add a cup of coffee or tea, or other drinks for the kids. We halved the quantities of ingredients in the recipe but we still ended up with a whole tray of cake and I froze most of it. You can see that our cake was a bit thinner than the recipe intended – so we didn’t have enough Streusel to completely cover the top. It looks a bit bald but it’s delicious. I can easily sneak a piece out of the freezer, and after about 30 seconds in the microwave it becomes my second breakfast, or my daughter’s after-school snack. So much for the socializing…

7. Look for some stories about the cake

The German romantic poet Eichendorff visited Schlesien in 1857 and wrote in a letter home: “Heute ist der Kirchweihfest der Schlosskapelle, es gab daher einen grossen Streuselkuchen zum Frühstück.” In English he would be saying: “Today was the castle chapel’s consecration day, so there was a large Streuselkuchen for breakfast.” Breakfast?! Well, I’ve had cake as part of breakfast in Germany before.

Schlesischer Streuselkuchen is the only cake I know which has a whole poem dedicated to it. It was written in dialect by the Silesian poet Hermann Bauch (1856-1924). This is the 6th out of 8 verses he wrote about “Schlaescher Straeselkucha”:

Wiel die Müdigkeit mich packa

Koch’ ich mir an Koffee risch,

Tunk derzu meen Straeselkucha

Und do bien ich wieder frisch.

Koan ich ei der Nacht nich schlofa,

Rück’ ich mir a Tallar har,

Assa sieba Streefla Kucha

Und do schlof ich wie a Bar!

Basically the poet is saying this: if he feels tired he grabs a coffee and dunks his Streuselkuchen into it, then he feels lively again. If he can’t sleep in the night he gets himself a plate, eats seven pieces of Streuselkuchen and then sleeps like a bear. Hmmm. The first idea makes sense but I’m not sure about the cure for insomnia.

Do you use cooking for learning or practising a language? And do you know any interesting stories behind the cakes you make?

Leave a Reply